Open Intelligence and the Evolving Threat

On 6 January 2021, the world watched as a large crowd of protesters violently made their way past police lines and into the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C., posting videos and photos on social media throughout the riot. The night before, also in D.C., another as-of-yet unknown individual placed two pipe bombs close to the Democratic National Committee headquarters and Republican National Committee headquarters.

In April 2021, the UK’s Security Service (MI5) warned that more than 10,000 UK nationals, including staff in government departments and key industries, were approached over the past five years via social networking sites by hostile state actors who sought access to sensitive information.

The common thread that ties these threats together is the candidness with which these events played out across open and public online forums and social media platforms. In completing threat assessments, we may unfairly favor confidential, closely held sources of information that appear to give us an inside track on a threat. But focusing on insider information instead of sources that are openly available to all can blind us to the obvious.

As the above examples highlight, adversaries can be very open about their intentions and objectives, often using social media or other public forums to post about future actions. Traditionally, the remit of physical security encapsulates the bounded space, employing a range of measures such as cameras, access control, perimeters, and intruder detection systems. A gap exists in managing the security of assets within the site and assessing the threats beyond it. It is not enough to produce a one-off threat assessment; there is a clear need for a more dynamic approach to identifying, assessing, and managing threats.

Part of the solution in bridging that gap to effectively ascertain and surveil threats beyond a site’s perimeter is developing and incorporating open-source intelligence (OSINT) capabilities.

While OSINT began as a discipline within the intelligence community, it was quickly adopted in the cybersecurity field. However, cybersecurity professionals largely highlight aspects of the OSINT process that are most applicable to cybersecurity, such as cyber threat intelligence. It would be a mistake to think cybersecurity OSINT is the totality of what OSINT entails.

OSINT is first and foremost an active process and thinking style. In practical terms, open-source information is the collection of publicly available information from open, freely accessible sources.

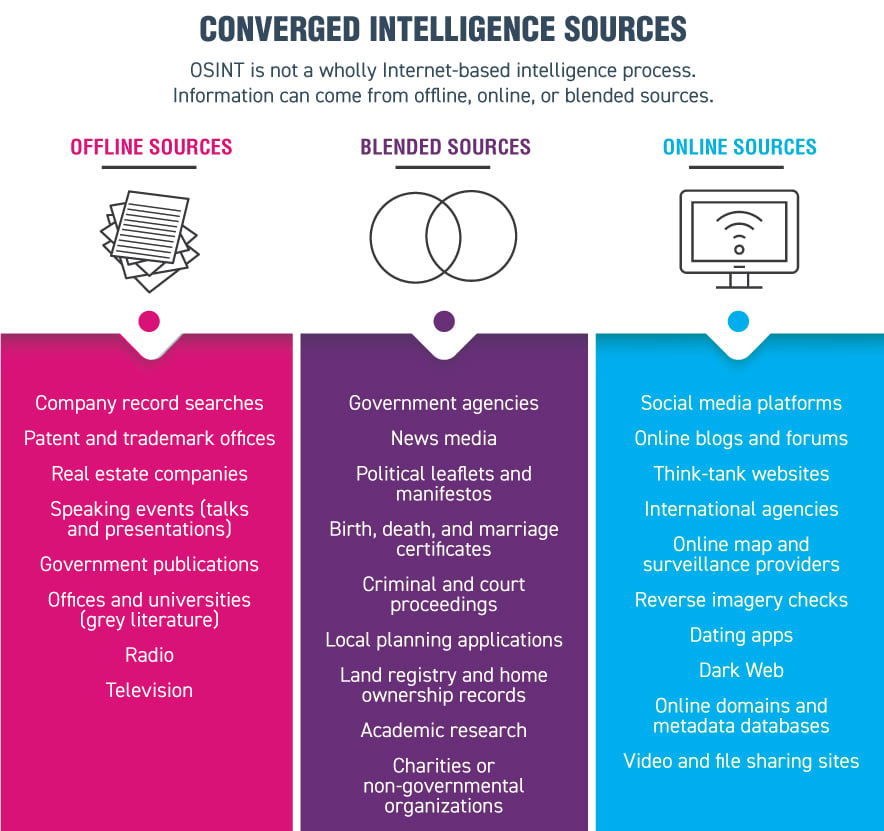

But information alone does not equate to intelligence. Intelligence is information with value added through analysis and assessment, disseminated in a timely manner to answer a key question or requirement. OSINT can include both online and offline materials—it is not a uniquely Internet-based methodology.

Threat assessments are just one part of the overall suite of security management practices for identifying and mitigating risks. Criteria for structuring threat assessments vary by virtue of the threat actor, the nature of the intersecting risk, and the type and value of the asset. However, threat assessments largely follow the core concepts of threat identification, ascertaining threat capabilities, and managing the assessed threat. The threat assessment process must become more dynamic to better manage and understand not just the threat, but the threat’s evolution.

Once completed, threat assessments are at immediate risk of becoming static statements and summaries; over time, the positive effect of threat assessments as a means to inform the risk and security posture of an organization become less effective or obsolete.

While the wider political drama of the U.S. presidential elections played out over months, the activities around ideation, planning, and action leading up to the 6 January U.S. Capitol riots may have occurred over only weeks. OSINT offers the ability to shift the threat assessment from a static statement into a dynamic cyclical process—a continuous threat assessment.

There is a need to regularly and actively re-evaluate intelligence as new questions arise, assumptions are challenged, and new information comes to light. This cyclicality is what makes OSINT an active process and thinking style—not merely a “check the box” exercise. By incorporating OSINT into threat assessments, a framework can be structured around the core aspects of the intelligence cycle—clear planning and direction, a managed collection strategy, processing information, structured analysis, and, finally, disseminating intelligence to key decision makers so they can take action.

OSINT should seek to build a profile of the areas where threat actors are active, such as forums and discussion boards, which would help map their intentions. As those sources of information inform the assessment process, they also establish the network to enable continuous monitoring and reporting, facilitating the routine updates security managers need for decision making and security posturing. The threat assessment becomes a living document, highlighting the social networks and online spaces where the threat actors are active. The result is a combined outlook of threat capabilities and a vital list of sources that can continually monitor and report information.

Determining the right places to look for such information can first appear daunting, but using the intelligence cycle will help narrow the search. Ideologically extremist groups, for example, seek to deliver their message to the public. In doing so, groups create portals between their covert operations and publicly available outlets. An adept OSINT process will help identify these portals, glean information of value, and provide intelligence input to a threat assessment.

A Clear Direction

Incorporating OSINT into threat assessments should lead with a focused direction aided by clear planning. The quantity of data and information available will mean that without effective direction and planning, an unstructured threat assessment exercise will inevitably flounder when wading through vast volumes of information. Direction—consisting of a specific query—helps set the groundwork for an OSINT investigation, and it will affect the success or failure of the threat assessment exercise.

The query should be realistic and practical. The direction should not attempt to steer the OSINT investigation to predicting the unpredictable or quantifying the obvious—for instance “when will the next pandemic occur,” or “will there be a terrorist attack in Europe within the year.” Taking the latter, given the breadth of terrorism risks within Europe, a terrorist attack within the year is a near certain occurrence. Pursuing these thought exercises does not help inform how we manage the risk, likely timescales, or types of attack.

Specificity is key to relating the threat to an organization, while also having the added benefit of focusing the search parameters of the OSINT stream. For example, terrorism is too wide a threat—narrow the focus down to a particular terrorist group, modus operandi, or location. Framing the wider understanding with focus on the specifics of the threat will add value to the outcome of an OSINT assessment in terms of turnaround time and resource management. Multinational organizations, for example, cannot rely on a threat assessment that seeks to capture a terrorist group’s global ambitions or lists the number of attacks.

OSINT planning calls for breaking down the key information required into more manageable parts. Exercises in probabilistic thinking will help manage the OSINT threat assessment into its key parts. Probabilistic thinking can be both a quantitative or qualitative practice and seeks to identify the most likely outcome from an event among multiple likelihoods. It is the act of building up sources of information and knowledge around possible outcomes to try and reduce the element of uncertainty as much as possible.

Planning a threat assessment around OSINT methods should initially quantify what is known, what can be learned, and the unknowable, while teasing out any biases, all of which will affect the threat assessment outcome.

Biases are an inherent part of assessments. They can lead to the wrong conclusions, so the information, our views, and our statements should constantly be challenged to identify what is actually important. There are many identified knowledge biases, such as anchoring and availability biases, which place an over-reliance or over-emphasis on the first available piece of information or drive assessments based on the immediate information to hand.

The speed of new information generated online and the resource demands on physical security departments underline how OSINT investigations are made in a continuously volatile and dynamic environment—both online and outside of the Internet. Planning will significantly signpost the areas where you need more information and where you need less, mitigating the risk of interference from bias. Additionally, probabilistic thinking in the planning stage will help navigate the problems of accuracy in dealing with inherently unreliable information—whether that’s social media, disinformation, or deliberate obfuscation.

Collection Strategy

The next stage is to establish the collection strategy, the value of which will be built off of earlier work during the direction and planning stages. There has been significant growth in commercial OSINT gathering platforms and products in recent years—a trend that is likely to continue. From forensic browser software to continuous geo-fencing for social media triggers to commercial satellite imagery, there is most likely a commercial collections platform catering for your specific security needs.

Myriad areas will govern the type and extent of the OSINT collection strategy. Some will be practical considerations—how many team members are free to spend time collecting information or what technical resources are in place to enable both information collection and routine security responsibilities. Accurate planning of OSINT and threat assessment requirements up to this point should ensure that the capabilities and demands are as evenly matched as possible. For instance, would the general media and public relations information from a threat group sufficiently answer key threat assessment questions, or is there a need to be involved in an online forum actively used by members of that same group? Understanding where additional effort is required can help identify efficiencies.

Additionally, there are clear safety, security, and organizational considerations to address long before executing information-gathering activities. A collection strategy should account for any deterrents—legal, financial, or reputational—that may impede the work. Risk appetites, ethics, and moral considerations all play a part in determining appropriate OSINT activities. Consider the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which a political firm harvested tens of millions of users’ personal data from Facebook. Although the action was legal, it had long-term reputational and data privacy implications.

Flexibility is important. As part of the organization’s security practices, threat assessments might only be an annual exercise. Like with the U.S. Capitol riots, however, the subject of the threat assessment could change weekly, and the security response will depend on the level of information secured from the collections plan, which may need to change to keep up. Building in flexibility enables adaptability.

Threat assessments can be subjective exercises, and there may be additional signals within the collected information that signify a change in interpretation is required. Consider how rapidly social justice movements and protests spread worldwide—massive social unrest can start from subtle events half a world away, triggering local tensions and sparking disruption. Events do not happen in isolation, and everyday ordinary signals can come to mark the start of world events. With the information we collect, we should be constantly looking to see how even the small pieces could impact our understanding.

Online entities, including social media, are making personal and professional information freely available on a massive scale, providing real-time access to imagery of localities, records of local events, as well as details of subjects’ social and professional contacts. The value of such information cannot be overstated. Online and offline social engineering attacks are built upon the freely available, in-depth personally identifiable information (PII) that exists across numerous platforms, including social media.

An OSINT collection strategy will inevitably touch upon PII, and—depending on the legal frameworks you are operating under—organizations will need to consider how such information is identified, recorded, and stored.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a wide-reaching and wide-encompassing document governing PII and its use. Exemptions exist for OSINT activity as it pertains to national security and law enforcement (which have separate directives). However, there is no specific or general exemption under GDPR for commercial or private security management work. As such, if you, your organization, or the subject of an OSINT investigation resides in the EU, investigators will likely have to reckon with the GDPR. Additionally, the GDPR equally applies to the processing of personal data online or offline, whether in social media, employment, or government records.

Under the GDPR, an OSINT investigation will likely need a legal basis for processing PII, and it should apply certain principles on how it is processed, such as data security, accountability, and governance, as well as identifying and incorporating the subject’s rights. Compliance requirements, from GDPR to an organization’s capacity for data storage, underline how available resources will be a key consideration.

One of the most frequent asks from OSINT, even by other OSINT practitioners, is the need for a list of tools, as though such a list will lead to direct success. It should come as no real surprise that there is no one OSINT program list or resource that will do it all. Rather, OSINT practitioners will usually build up personal knowledge of tools, useful sites, and a network of OSINT practitioners that fit their specific needs. When deciding what collection methods and tools to use, overriding consideration should always be given to safe security practices, while keeping in mind the legal, personal, moral, and ethical implications of engaging in OSINT collections methods. The adverse legal implications may apply equally to the OSINT analyst and the organization.

Process and Analysis

Given the wide variability in types of information and concerns over its reliability and credibility, processing is an integral element to OSINT.

Where the required information is amenable to primary and secondary sources, look to reach for the former: direct eyewitness evidence is worth more than third- or fourth-hand information, and we should grade the information as such. Where threat assessments necessitate OSINT investigations into more uncertain areas, such neat classification of sources may not always be readily available. As such, OSINT investigators should consider the Admiralty or NATO System to help evaluate the collected information.

Under the Admiralty System, information is judged on reliability—based on the source’s past reporting, whether there are doubts about its authenticity or trustworthiness, and the competency of the source. Information judged on reliability is graded A through F. Credibility is assessed against whether the information can be corroborated against other sources or against what is already known about the matter. Credibility is graded with a numerical value between 1 and 6.

If an eyewitness to a popular event provides direct, first-hand information that can be checked against other sources, for example, that source would be graded A1. A person reporting information that they have overheard but have no direct experience of—and they are reporting for the first time—would likely be graded F6.

The purpose is to build confidence in the accuracy and reliability of gathered information by using the different grades to add nuance and context to pieces of information and better inform decisions.

There is an inherent risk in any method of information collection to always want more—more time or information with which to make decisions. A fatal risk for the OSINT threat assessment can materialize by coming to a conclusion too early or failing to come to any meaningful conclusion at all. Information collected, processed, and analyzed via OSINT methods will invariably change, and it will never remain static. An OSINT-led threat assessment inherently enables dynamic monitoring over a static statement of intent.

Delivery

The final component is the delivery of timely, relevant, and actionable findings to key decision makers, be they within the physical security remit or wider executive leadership positions. Invariably, there are in-house writing style requirements, but they should not impede conveying the key judgments and important information effectively to a reader who may not have time to read an entire assessment in detail.

Ideally, the assessment should be written for the person or department that requires it. For instance, undertaking a threat assessment for a member of staff traveling overseas may simply require a cover page with the key findings for his or her manager while the body of the assessment remains within the relevant security department. In other cases, a threat assessment may be forwarded to an internal investigation department or a wider audience, in which case the assessor may seek to withhold certain aspects or findings until later. A formulaic process will fail.

OSINT is an evolving framework, ideally suited to dynamically assessing evolving threats. The challenge of unreliable information, especially in today’s age of disinformation, is not insurmountable. Additional issues remain, such as managing people’s expectations of the OSINT process, the requirements for training and technology, and resource allocation. However, employing the intelligence cycle as part of the threat assessment process will help make the most of resources at hand within the time available.

Mark Ashford works in security risk analysis and threat assessment in the financial industry, following a 12-year background in law enforcement and state security. His other areas of interest include intelligence analysis, strategic foresight, and international relations.