Turbulent Times Create New Waves in Public Safety Surveillance Trends

It would be an understatement that the last year has been one of the most turbulent in recent history for public safety. Public safety departments have been faced with increasing scrutiny and threats of defunding, limiting crowd control agents, or abolishment of departments. Public opinion has polarized acceptance of public safety policies and procedures.

It would be an understatement that the last year has been one of the most turbulent in recent history for public safety. Public safety departments have been faced with increasing scrutiny and threats of defunding, limiting crowd control agents, or abolishment of departments. Public opinion has polarized acceptance of public safety policies and procedures.

With all of this turmoil, the public must still be kept safe. One of the tools that public safety departments use to accomplish this is surveillance. Many public safety departments have used cameras for security and surveillance in many ways in the past. While it is still business as usual, it is also time to look at new trends in public safety surveillance.

Types of Surveillance

Public safety surveillance incorporates a multitude of cameras that can be used, and those cameras may have stipulations. While terms like “Big Brother” may be thrown around, if deployed correctly public safety surveillance can be a great tool and provide irrefutable evidence. If a “picture is worth 1,000 words,” a video recording in evidence is worth five to ten years.

Citywide Surveillance. Citywide surveillance puts camera resources in high crime locations, or points of public interest such as locations of high occupancy due to tourism.

Citywide surveillance has become available primarily in the last 12 years as Internet protocol (IP) security cameras that use Power over Ethernet (PoE) have proliferated the security market. Today, an IP camera can be installed on a pole with a cellular router (this incurs data charges that may prevent live viewing), a mesh radio, or directly connected to city infrastructure for video where public safety needs it—not just on a building.

Citywide surveillance may include fixed cameras, Pan-Tilt-Zoom (PTZ) cameras, multisensor cameras (3-4 fixed cameras in one dome), and Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) cameras. Citywide surveillance allows public safety departments to allocate officers where they are needed with less cost. A Control Center or a Real-Time Crime Center (RTCC) allows a minimum number of trained officers to direct patrol officers or field officers where they are needed. They operate as incident commanders until the patrol officer arrives on-scene.

Body Worn Cameras (BWC). The BWC trend has been going on for a while. While this market has been captivated by a few highly successful companies, traditional surveillance camera manufacturers have stepped into this space and offer a BWC that records directly to the existing Video Management Systems (VMS). For many departments, this has been a welcome addition.

Many departments are finding that it is a constant resource drain to redact BWC video, as well as a cost problem due to the ongoing contract and long term video retention costs. Redaction is necessary when there are minors or bystander(s) that is not part of the incident. While some BWC manufacturers have built this into the application, for others the redaction process may involve a number of manual actions by staff to ensure the redaction follows the movement of the persons. Some manufacturers have inverted this process to redact the entire scene, and then un-redact the individual(s) of interest.

While many public safety officers first dreaded this technology, it is irrefutable that this technology has saved both the officer and the public on multiple occasions. Many officers refuse to go to work without their BWC recording today. Charles Katz, director of Arizona State University’s Center for Violence Prevention and Community Safety and an expert on body-worn cameras, has said “Now many police officers argue they won’t go out on the street without body-worn cameras. They want that as evidence they are doing the job right.”

According to a 10-year study published in 2020 by the National Police Foundation, officers who wear body cameras consistently appear to have fewer complaints filed against them than officers without cameras.

Incident Specific Video. VICE, SWAT, Loss Prevention, and other law enforcement teams use incident specific video such as covert camera solutions, aerial platforms, or drones equipped with cameras to provide detailed video from various views for surveillance and officer safety.

The trend of using drones or “Unmanned Aircraft Systems” (UAS) is only going to continue. Drones are being used to search buildings prior to officers’ entry. Drones are being used for aerial video platforms to provide SWAT officers a full view of barricaded subject’s surroundings. Drones are also being used to hunt and capture smaller “suspect” drones. Forbes released an article in 2019 of the top 10 ways police are using drones today, as well as recently Security magazine hosted a public private partnership webinar where police tested drone use with the partner during COVID-19 when buildings were empty to provide real world training. Due to the continued growth and use of drones, the International Chiefs of Police (IACP) have released guidelines and model policy for police departments on the use of drones.

Policy Requirements

Policy requirements for surveillance video are not new. Public safety departments have internal policies that affect surveillance video. Many department policies are often the reaction to a specific incident that has occurred; additionally policies are created because a local or state court case prompted the change. Many departments, both public and private use guidelines and model policies written by the IACP. Policies must then be sent to the police attorney’s office or general council to be approved for implementation.

New policies are often created or influenced by public interest groups, including the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), National Association of Police Organizations (NAPO), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Rifle Association (NRA), and Black Lives Matter (BLM). These policies stem from the overall concept of police reform, which in the modern era dates to the passing of H.R. 3355, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Since the enactment of this bill, many public interest groups have taken the opportunity to enact or influence policies to accelerate reform. Many police departments have experienced a growing trend of reform that is being leveraged to affect surveillance video.

For instance, a new policy could be that all PTZ cameras are on tour, to prevent a biased video recording of one specific location. The problem with this is that a PTZ camera only records where it is pointed, and it is rarely pointed in the direction where an incident occurs; or quickly moves away while an incident is occurring. To overcome this, many departments are looking at multisensor fixed cameras to provide general overviews or collocated multisensor and PTZ cameras.

Another example policy could be requirements that all camera interactions be logged for a period of at least three years, and be viewed by a sworn employee of rank higher than a patrol officer. To answer this, many VMS applications offer searchable databases to include date and times users access the system.

Other policies could require camera data to be retained for a fixed maximum of days. This may differ between BWC video and in-car camera video, and citywide surveillance video. All bookmarked video data must meet department defined retention requirements. While the security industry standard is 30 days, many cities are limited to 10 or 14 day maximum for citywide surveillance. These limits are again part of police reforms to prevent police departments and officers from having access to video that could create bias or extend outside a reasonable timeframe to report a crime. Reasonableness here may be defined either by a public interest group, internal policy, or others.

The key here is that some public safety departments may face public interest groups that affect internal policy.

Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS)

Criminal Justice Information (CJI) is defined as information that is collected by criminal justice agencies and that is needed for the performance of their legally authorized and required functions, such as criminal history record information, citation information, stolen property information, traffic accident reports, wanted persons information, and system network log searches. CJI does not include the administrative records of a criminal justice agency.

Specifically for video, once video has been recorded, it must now meet CJIS compliance to be admissible in court. An absolute way to meet CJIS compliance is to record locally to on-premise servers. While this has been the preferred method in the past, many departments are looking to utilize Software as a Service (SaaS) or cloud hosted models. There are reasons for this; some are IT mandated, others are cost related. Whatever the reason, any digital evidence—including video—must keep CJIS compliance. Some cloud solutions are CJIS compliant, the majority are not; this goes for both Digital Evidence Management (DEMS) and VMS. Failure to meet CJIS compliance may leave digital evidence with a broken chain of custody and make it inadmissible in court.

Visualization Applications

There is a trend in public safety to visualize data from disparate data sets into one “single pane of glass” view. In the past, these have been called Physical Security Information Management (PSIM) tools. The problem with that statement is that PSIMs do not offer the connected applications and situational awareness that public safety departments need.

PSIMs typically connect VMS and access control to a single solution. For public safety, these visualization platforms need to connect to open-source data, weather data, internal surveillance camera data, Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) data, possibly public-private partnership data, city gunshot detection, and more to provide accurate data that allows for a stationary supervisor to be the incident commander until resources arrive onsite. Visualization tools provide real-time access to a multitude of disparate datasets that provide situational awareness and increase officer safety.

Many of these platforms include analytics that automate workflows so that a “hit” from one dataset will trigger secondary and tertiary actions from additional datasets. Many of these visualization applications now offer a virtual sandbox for public safety departments to conduct real world tabletop exercises with real world outcomes.

Information as a Service

More than100 countries today have some type of freedom of information law that allows public records to be requested or released. It cannot be discarded that information requests are a trend today. In most cases, the burden of proof falls on the entity that the information is requested from—not the person requesting the information. The person making the request does not usually have to explain their reasoning for the request, but if the information is not disclosed a valid reason must be given.

Where freedom of information requests differ is that many public safety departments can have certain evidence excluded. Some departments can have BWC video excluded, while others may be required to redact BWC video. Citywide surveillance may be subject to freedom of information requests as well.

Partnerships

Public safety departments in good years were impacted by limited funds. Today, those funds are even more limited. The ability for public safety departments to build successful public-private partnerships (P3s) is critical for departments to expand. P3s may involve sharing of surveillance cameras with City Transportation Departments (CDOT) or transit departments to stretch the city dollar further by using existing infrastructure or IT resources—instead of duplicating work and costs.

Additionally, P3s have become a useful tool for public safety departments to provide surveillance cameras in areas where they are needed and offer a myriad of advantages to P3s. One thing to note is that each department should have or create a standard Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that is signed by each partner. MOUs are designed to protect both parties; but note that some partners may not agree and this would prevent a successful partnership.

Traditional MOUs include a Scope of Agreement; whereas public safety equipment is not to be accessed by the private partner, nor does having a partnership with the public safety department warrant special privileges for the private partner. The Scope of Agreement typically involves a mutual waiver of liability, and gives the private partner full rights to request removal of public equipment within a reasonable amount of time. Depending on technology, there may be multiple MOUs in place for the same P3. When possible it is best to have the police attorney draft the MOU and submit to the private partner. Any changes to the MOU must be approved and signed as per the agreement.

Failure to have a successful MOU may put the public safety department at risk if damage to the private partner occurs. It is always good to check the date on MOUs as well, as many expire after one year. When working with P3s, it is imperative to determine if partner video is exempt from freedom of information requests. This may have impacts on the partnership, as well as how the shared video is stored.

Analytics

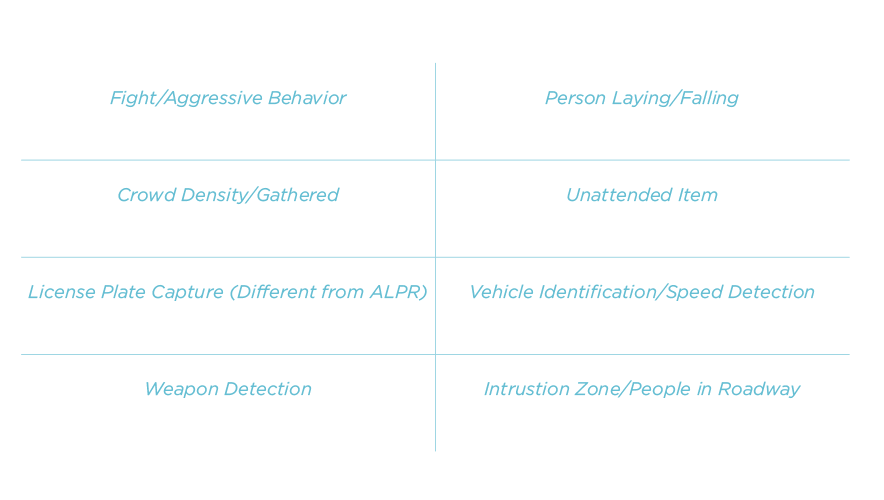

Camera analytics are a huge trend in public safety surveillance. While traditional surveillance analytics such as line crossing, people counting, and perimeter protection may not apply to public safety video, specific analytics may apply. Many analytics are based on artificial intelligence (AI).

AI is best described by Eda Kavlakoglu, product manager with IBM, as a Russian nesting doll. AI is the outer doll; the next layer is machine learning—a subset of AI, where the appliance learns what the scene. Neural networks and deep learning are subsets of machine learning and are used to build more robust AI models.

Two truths must be mentioned about AI models. One, AI models must be learned properly by the equipment. Just like a toddler who is left to teach themselves, they will become an unruly teenager. AI must be taught and confirmed repeatedly to ensure anomalies do not become common. Bad data in unchecked will bring bad data out. Two, any changes in the scene requires the AI to be retaught. If a camera is moved or turned, either intentionally or by accident, it will require the AI to learn the new scene. Analytics are being used to provide actionable data to public safety by spotting anomalies otherwise not observed without a human interaction.

Cameras by nature are a reactive tool, recording up to 60 frames per second. Video analytics help a camera become proactive by processing data—that previously required a human interaction—in a split second to identify and alert users based on pre-defined and learned behaviors. For instance, analytics could detect and then alert users about the following behaviors:

Facial Recognition

Facial Recognition offers great value and is being widely used; however, the term has been overly used for multiple products. In regards to video analytics there are two facial biometric analytics to consider.

Face Matching. This is software that takes a known picture and scans recorded video for a likeness. Anything over a 75 percent hit is flagged as a possible match. This requires human interaction to review, accept, or throw away. It is a great technology for investigations, tracking where a person was last seen, or for tracking in a stadium/retail applications for buying trends.

Facial Recognition. This software requires a known picture or a learned picture to be “recognized” in real-time and then follows an automated workflow to alert security, initiate lockdown, etc. If the software has an accuracy rate between 85 percent and 93 percent, it is a good response. But there is no industry standard nor is there a required percentage of accuracy for use, allowing the technology manufacturers to dictate accuracy. This has forced some cities and countries to discourage public safety departments from using the technology. It is dependent on the public safety department to address deficiencies of the technology.

Capturing evidence of a crime occurring via surveillance video is part of public safety. How this is accomplished will grow and change as often as technology changes. As technology trends speed up and change so will the requirement for public safety to meet those trends.

Jon Polly, PSP, IC3PM is the chief solutions officer for ProTecht Solutions Partners, a security consulting company focused on smart city surveillance. He has worked as a project manager and system designer for city-wide surveillance and transportation camera projects in Raleigh and Charlotte, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; and Washington, D.C. He is certified as a Physical Security Professional (PSP) by ASIS International and a Critical Chain Project Management (IC3PM) by the International Supply Chain Education Alliance (ISCEA).